Grand Tour guides to Rome

July 18th , 2016 Tagged with: Charles Dickens • early guidebooks • English poets in Rome • Grand Tour • Nathaniel Hawthorne • Romantic poets • Rome • study abroad

authors Mary Jane Cryan and Fulvio Ferri

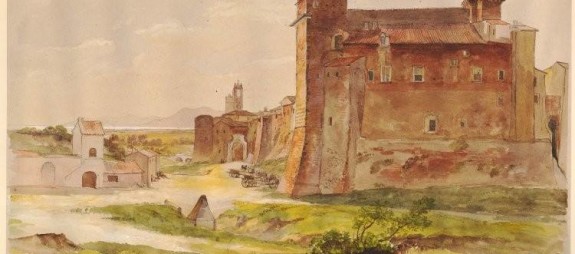

Eyewitness Guide to Rome, which I helped write in the 1990s when I lived in Rome near Castel Sant’Angelo, is full of colorful illustrations and maps. It is a far cry from Grand Tour guides and the first English guidebook to Rome, “Ye Solace of Pilgrims” written by John Capgrave for the Holy Year of 1450.

In the 16th century English poets Spencer and Milton praised classical Rome but also expressed antagonistic sentiments since these were the years King Henry VIII was breaking with the Church of Rome. Nonetheless the English were fascinated by all things Italian; Palladian style country houses and Italian gardens.

The founders of the Romantic Movement, Wordsworth (in 1838) and Coleridge (in 1804-6) both visited Rome and Shelley wrote beautiful lyrics inspired by the Italian sky while living on Via del Corso but his private letters showed his disgust with Rome.

Lord Byron also had ambivalent feelings about the city: enthusiastic and rhetorical in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (“O Rome!My country, city of the soul!”) while he criticized Italy and Italian customs in his private letters .

Poor Keats, who came to Rome seeking relief from the tuberculosis that was killing him, died within the year. The icy cold tramontana winds and drafty palazzi are still treacherous nowadays.

When Charles Dickens arrived in Rome on January 30, 1845, by way of Genoa and other northern cities, it was a rainy, muddy day at the beginning of Carnival time. His description of St. Peter’s square shows his enthusiasm.

“The beauty of the Piazza in which it stands, with its clusters of exquisite columns, and its gushing fountains -so fresh, so broad and free, and beautiful – nothing can exaggerate…the first burst of the interior, in all its expansive majesty and glory; and most of all, the looking up into the Dome is a sensation never to be forgotten.”

Dickens described his wonder at the Easter illumination of St. Peter’s dome when scampering workmen, the sampietrini, risked their lives to simultaneously ignite burning flares which outlined the cupola against the night sky.

“…the whole church, from the cross to the ground, lighted with innumerable lanterns, tracing out the architecture and winking and shining all round the colonnade of the piazza…every cornice, capital and smallest ornament of stone expressed itself in fire and the black solid groundwork of the enormous dome seemed to grow transparent as an eggshell.”

From St. Peter’s, Dickens had his coachman bring his party to the Colosseum arriving there in a quarter of an hour, much quicker than we could do it with today’s traffic.

“To see it crumbling there…its walls and arches overgrown with green, its corridors open to the day, the long grass growing on its porches, young trees of yesterday springing up on its ragged parapets and bearing fruit…to see the peaceful Cross planted in the center, to climb into its upper halls and look down upon ruin, ruin, ruin all about it…is to see the ghost of old Rome, wicked, wonderful city, haunting the very ground on which its people trod.”

Also American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne was taken by Rome and described his visit to the Colosseum in the pages of The Marble Faun written after his 1858 stay in the Eternal City. The author of The Scarlet Letter and House of Seven Gables found himself in quite a different element during his evening visit to the great amphitheatre.

Also American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne was taken by Rome and described his visit to the Colosseum in the pages of The Marble Faun written after his 1858 stay in the Eternal City. The author of The Scarlet Letter and House of Seven Gables found himself in quite a different element during his evening visit to the great amphitheatre.

“As usual of a moonlight evening, several carriages stood at the entrance of this famous ruin and the precints and interior were anything but a solitude…There was much pastime and gaiety just then in the area. On the steps of the great black cross in the center of the Coliseum sat a party singing scraps of songs with much laughter and merriment between the stanzas..it was a strange place for song and mirth. That black cross marks one of the special blood spots of the earth where the dying gladiators fell thousands of times over.”

His remarks on the pacific co-existence of religion and merriment also bring him far from his themes of Puritan New England.

“… in Italy religion jostles along side by side with business and sport and people are accustomed to kneel down and pray, or see others praying between two fits of merriment or between two sins.”

Hawthorne had a love-hate relationship with Rome for he had caught cold upon arriving by carriage from the port of Civitavecchia and his daughter, Una, almost died with a flu she caught staying out late to sketch in the Forum.

In his notebooks he pondered on the mouldering palazzi, the filthy streets, the beggars and ragged children but when the sun came out Rome became for him “a poetic fairy precint” where he gained inspiration for his new novel while exploring the Borghese gardens and wandering among the marble statues of the Capitoline Museums. He found Rome growing on him,

“..No place ever took so strong a hold of my being, nor ever seemed so close, so strangely familiar”.

After having kept himself aloof during the Carnival that first year in Rome, Hawthorne fully participated in the next year’s festivities and he began wondering how he and his family would live back in their New England village where “…there are no pictures, no statues…Rome certainly does draw into itself my heart as I think even London or even little Concord or old sleepy Salem never did and never will.”

While Italian writers were complaining about Papal censorship Hawthorne enjoyed freedom of expression, “Rome is not like one of our New England villages where we need the permission of each individual neighbor for every act that we do, every word that we utter, and for every friend that we make or keep. In these particulars the papal despotism allows us freer breath than our native air.”

Together with the author of Moby Dick, Herman Melville, Hawthorne snubbed the artistic gathering place, Caffè Greco, for they both disliked the smokey, bohemian atmosphere.

Melville however did frequent the Lepre trattoria across the Via Condotti where the foreign artistic colony ate economically and met friends. How envious are we when we discover that he dined at the Lepre for 19 cents and how we sympathize with his remark that he was “fagged out completely” after a first cursory visit to the Vatican galleries.

Trattoria Lepre, unfortunately, no longer exists and Via Condotti has become one of Rome’s most expensive shopping streets but the Caffè Greco and another historic landmark, Babington’s Tea Rooms, are still there at the bottom of the Spanish Steps serving out cakes, tea and atmosphere.

Between 1863 and 1868 the American Legation was located in the back room of a private banking firm on the same premises now occupied by Babington’s. Because of the area’s concentration of Anglo-Saxon creative people it was known as the English Ghetto and signs of the passage of many well-known writers and artists are still to be found there.

The Brownings, Robert and Elizabeth,lived at number 41 Via Bocca di Leone; Keats in the house that is now the Keats-Shelley Memorial at the bottom of the Spanish Steps,the painter Turner had rooms at number 12 Piazza Mignanelli where a fast food restaurant stands today and James Joyce, still an impoverished bank employee, lived on Via Frattina with his family.

In 1867 Mark Twain visited the city that he called “a museum of magnificence and misery”. Slowly he learned to like Rome and adopted the Romans’ lifestyle as he “began to comprehend what life is for”.

Henry James, the very international American author, made his way to Rome in 1869 and paused at the D’Inghilterra Hotel, which is still on Via Bocca di Leone, just long enough to leave his bags. Then he ran out, criss-crossing the city on foot for about five hours “in a fever of enjoyment” and at the end of this first day in Rome wrote to his brother back in Boston,

“At last – for the first time- I live!”

Discover more about Rome and guidebooks on my blog

Lots more on historic travel in central Italy in my books . Order from the Books page.

Order directly for discount and author’s inscription.

If you wish to use any parts of this article (originally published in the 1970s, see Bibliography page) for research purposes, please request permission first from author : macryan at alice dot com and cite the author.

All the material on this website and my blog 50yearsinItaly are copyrighted.